In this post (in German), Nathalie Rudolph of the FGHO in Lübeck gives us an insight into her work on the backbone of the Viabundus map: the database with nodes.

Hinter den Kulissen: (M)ein Tag mit der Datenbank

Ein Werkstattbericht von Nathalie Rudolph (FGHO).

Das Viabundus Projekt hat sich zum Ziel gesetzt, eine online frei zugänglichen digitalen Karte von vormodernen Fernstraßen in Nordeuropa zu schaffen. Die Idee für diese Karte entstand 2017 in einer Tagungs-Kaffeepause. Mit dem erfolgreichen Pro*Niedersachsen-Antrag konnte es dann in Zusammenarbeit von IHLF (Uni Göttingen) und FGHO (Lübeck) mit einem Projekt zum Gebiet des heutigen Niedersachsen losgehen.

Für eine solche Karte braucht man jedoch eine Datengrundlage, in dem Fall Viabundus eine Datenbank mit „Nodes“ (Knoten), wozu wir von der FGHO in Lübeck die Vorarbeit geleistet haben. Wir von der Ausgangspunkt war die Arbeit mit dem Buch „Hansische Handelsstraßen“ von Friedrich Bruns und Hugo Weczerka von 1962, aus dem Friederike Holst, meine Vorgängerin, die „Nodes“ herausgesucht hat. Bei den „Nodes“ handelt es sich um Orte, aber auch beispielsweise um Häfen, Zölle und Jahrmärkte, die Land- oder Wasserstraßen verbinden. Seit der „Kaffeepause“ sind heute bereits 11.000 Orte in der Datenbank verzeichnet.

Jeder einzelne in den „Handelsstraßen“ genannte Ort wurde in die Datenbank eingetragen und für die Darstellung auf der digitalen Karte mit Koordinaten versehen. Eines der Hauptprobleme war dabei die Frage, wo genau diese Koordinaten zu setzen waren. Da Handelsrouten im Mittelpunkt des Projekts stehen, bot sich der historische Marktplatz oder Kirchplatz des jeweiligen Ortes an – doch wo befand sich der historische Marktplatz oder das historische Zentrum von z.B. Altona, Bardowick oder Flensburg? Vor allem in Siedlungen die verlegt oder verschwunden sind oder ihre mittelalterliche Siedlungsstruktur durch Industrialisierung, Stadtbrände, Kriegszerstörungen oder Stadtsanierungen weitgehend verloren haben, ist dies manchmal eine schwierige Frage und sie muss von Fall zu Fall neu beantwortet werden.

Mittlerweile sind die Mitarbeitenden in allen vier Teilprojekten damit beschäftigt, die „Nodes“ fortlaufend um weitere Informationen anzureichern, etwa zur Stadtentwicklung, Jahrmärkten und Messen, Stapelrechten und Zöllen. Die FGHO beschäftigt sich dabei zunächst mit dem Gebiet des heutigen Schleswig-Holsteins. Dafür können wir etwa Standardwerke wie das „Deutsche Städtebuch“ von Erich Keyser nutzen, das wohl bis heute umfangreichste Nachschlagewerk für die vormoderne Geschichte der Städte. Das „Städtebuch“ verzeichnet Informationen unter anderem über die Geschichte der Städte und der Siedlungen, aus denen sie hervorgegangen sind, beschreibt Handel und Wirtschaft bis in die Neuzeit und macht Angaben zu Einwohnerzahlen. Für meine Arbeit mit der Datenbank sind dabei folgende Infos wichtig:

• Die Angaben zu den verschiedenen Namen der Städte, damit sie in der Suchfunktion auch über alte, nicht mehr gebräuchliche Namen gefunden werden können.

• Die Angaben zum Ortsursprung und zur Siedlungsentwicklung, die zum Teil schon viel über die Geschichte eines Ortes und mögliche Relevanz für Handelsstraßen aussagen. So sind die Lage an einer Furt, oder Markt-, Zoll- und Münzprivilegien bereits Indizien für die wirtschaftliche Bedeutung eines Ortes.

• Die Angaben zur Stadtwerdung, darunter auch wer dafür verantwortlich war, aus welchen Gründen sich dazu entschlossen wurde und welches Stadtrecht tatsächlich verliehen wurde. Für Hamburg wird etwa auf die Verbindung der erzbischöflichen Altstadt und der Neustadt um 1215 hingewiesen, obwohl sie erst 1228 einen gemeinsamen Stadtherren hatten.

• Die Wirtschaftslage der Städte. Hier werden oft Zölle, Stapelrechte, Handelsprivilegien und auch Angaben zu Jahrmärkten gemacht. Für wichtige Wirtschaftszentren wie Hamburg sind diese Informationen selbstverständlich recht umfangreich: dieser Abschnitt geht über drei Seiten und beginnt mit der „Genehmigung des Landesherrn Grad Adolf III. von Holstein zur Anlage eines Alsterhafens u. eines Marktes für die Neustadt“.

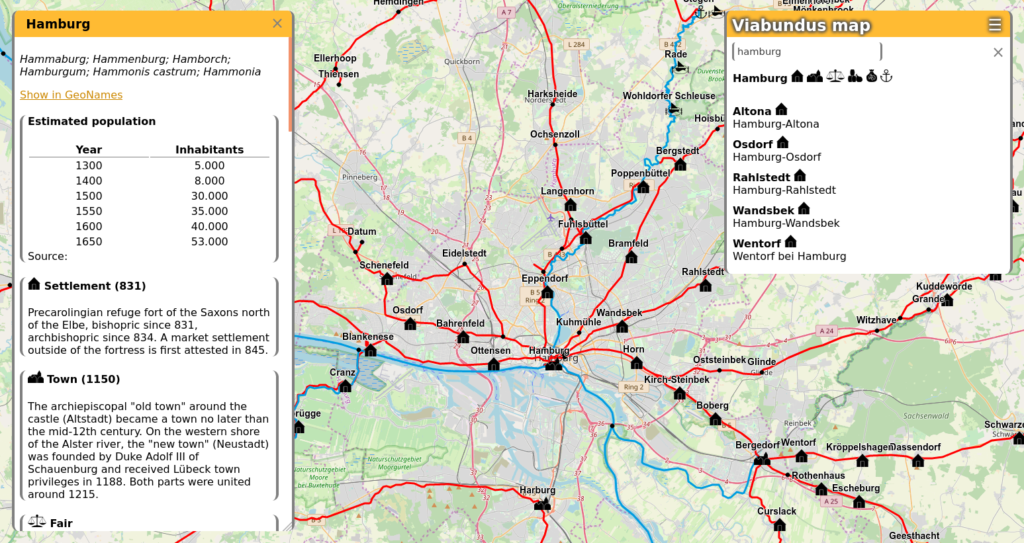

Diese Daten trage ich dann sowohl auf Deutsch als auch auf Englisch in die Datenbank ein. Zum Glück lässt sich diese Arbeit trotz Social Distancing gut im Homeoffice erledigen. Und sie ist notwendig, damit spätere Nutzer der Karte bei einem Klick auf die jeweilige Stadt die wichtigen Informationen gebündelt bekommen. Ein kleiner Vorgeschmack ist hier zu sehen:

Hope this helps – English Translation (with a little help from Google):

Behind the scenes: My/A day with the database

A workshop report by Nathalie Rudolph (FGHO).

The Viabundus project has set itself the goal of creating an online, freely accessible digital map of premodern highways in Northern Europe. The idea for this map came from a conference coffee break in 2017. With the successful Pro*Niedersachsen funding application, IHLF (University of Göttingen) and FGHO (Lübeck) were able to start a project on the area of today’s Lower Saxony.

For such a map, however, you need a data “foundation”, in the Viabundus case a database with “nodes”, for which we have done the preliminary work from the FGHO in Lübeck. Our starting point was the 1962 book “Hansische Handelsstraßen” (Hanse Trade Routes) by Friedrich Bruns and Hugo Weczerka, from which Friederike Holst, my predecessor, selected the “Nodes”. The “nodes” are places, but also, for example, ports, customs duties and fairs that connect highways or waterways. Since the “coffee break”, 11,000 locations have already been recorded in the database.

Every single place named in the “Trade Routes” was entered in the database and provided with coordinates for representation on the digital map. One of the main problems was where exactly these coordinates should be set. Since trade routes are at the centre of the project, the historical marketplace or church square of the respective location offered itself – but where was the historical marketplace or the historical center of e.g. Altona, Bardowick or Flensburg? Especially in settlements that have been relocated or disappeared or that have largely lost their medieval settlement structure due to industrialization, city fires, war destruction or urban redevelopment, this is sometimes a difficult question and it has to be answered case by case.

In the meantime, colleagues in all four sub-projects are busy enriching the “nodes” with additional information, such as about urban development, fairs and markets, staples and customs duties. The FGHO initially deals with the area of today’s Schleswig-Holstein. For this purpose, we can use standard works such as the “German City Book” by Erich Keyser, probably the most comprehensive reference work for the pre-modern history of cities. The “City Book” records information, among other things, about the history of the cities and the settlements from which they originated, describes trade and economy up to the modern era and provides information on the number of inhabitants. The following information is important for my work with the database:

• The information on the different names of the cities so that they can also be found in the search function using old, no longer used names.

• The information on the local origin and settlement development, some of which already say a lot about the history of a place and possible relevance for trade routes. Their location on a ford, or market, customs and coin privileges are already indicative of the economic importance of a place.

• The information on how to become a city, including who was responsible for it, for what reasons it was decided and which city rights were actually granted. For Hamburg, reference is made, for example, to the connection between the Archbishop’s old town and the new town around 1215, although it was only in 1228 that they had a common city ruler.

• The economic situation in cities. Customs, staples, trading privileges and also information about fairs are often made here. For important economic centers such as Hamburg, this information is of course quite extensive: this section has three pages and begins with the “approval of the lord Grad Adolf III of Holstein for the construction of a harbour on the River Alster and a market for the new town”.

I then enter this data in both German and English in the database. Fortunately, despite social distancing, this work can be done well in the home office. And it is necessary so that later map users can get the important information bundled by clicking on the respective city. A little foretaste can be seen here:

Wow, thank you very much for the translation!